THAT NAGGING VOICE IN THE BACK OF YOUR MIND

2020Site-Responsive Media Installation and Online Archive.

Prairie Ronde Artist Residency, Vicksburg, MI

THE FINAL INSTALLATION:

THAT NAGGING VOICE IN THE BACK OF YOUR MIND, 2020

Site-Responsive Digitally Projection-Mapped Abstract Animation on Fabric Sculptures and Windows, Sound, 20 x 24 x 20 ft, 4:30.

Prairie Ronde Gallery, Vicksburg, MI

Opened September 18, 2020

Site-Responsive Digitally Projection-Mapped Abstract Animation on Fabric Sculptures and Windows, Sound, 20 x 24 x 20 ft, 4:30.

Prairie Ronde Gallery, Vicksburg, MI

Opened September 18, 2020

THE ARCHIVE:

While in residence in Vicksburg, I want to connect to this place as much as possible. I know that exploration in the form of walks and drives, as well as conversations with people I meet here, will comingle with all the things, from global to personal, that I am processing internally. All of these will come together with my experience in the studio, influencing what I make in ways that are complicated, specific, emotional, political, and human.

Here, I compile documentation of these experiences: photos and thoughts, process images of the gallery installation as it develops. It is a collection of images and ideas. They seek to find what’s behind things, rather than to draw conclusions.

Here, I compile documentation of these experiences: photos and thoughts, process images of the gallery installation as it develops. It is a collection of images and ideas. They seek to find what’s behind things, rather than to draw conclusions.

As someone who’s been involved in twelve-step recovery for all of her adult life, self-inventory is indispensable. While most people would likely benefit from this kind of practice, many do not have a motivation so powerful as a potential relapse to motivate them through the pain of really looking at self.

In this time of quarantine, isolation, fear, and violence, the strategies I use to get through are honest sharing (vulnerability) and self-inventory. However formally or informally, anyone may choose to approach these practices; here I lay bare my experiences to offer as a resource, whatever that may be, for anyone who finds them meaningful or useful. At its best, I hope it will function as something between a journal and an archive.

In this time of quarantine, isolation, fear, and violence, the strategies I use to get through are honest sharing (vulnerability) and self-inventory. However formally or informally, anyone may choose to approach these practices; here I lay bare my experiences to offer as a resource, whatever that may be, for anyone who finds them meaningful or useful. At its best, I hope it will function as something between a journal and an archive.

On one of my first days in Vicksburg, I woke up, read for a while, and headed over to Prairie View State Park. It was the first time I’ve been swimming since last summer. While in the water, I spent some time sitting in the very shallows. I found small shells half-buried in the sand all around. I collected as many as I could hold in one hand. I’m not sure why. I remember collecting shells as a child at the beaches in Delaware and Maryland. As I collected shells, I a small fish was investigating me. I found it’s interest sweet and enjoyed watching it interact with my legs and feet. Eventually, it had a friend join in. I felt somehow included in their ecology for the time I was with them and appreciated the fleeting sense of connection.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the police. In Chicago, from the time of George Floyd’s murder until I left for Michigan, there were so many charged and violent exchanges between demonstrators and police. My roommate was active in organizing during this time, especially with the campaign for the Civilian Police Accountability Council (CPAC). Through their experiences, I learned how the police showed up, as a matter of routine, to peaceful actions dressed literally for war - in full riot gear with batons, tear gas, and mace all at the ready.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the police. In Chicago, from the time of George Floyd’s murder until I left for Michigan, there were so many charged and violent exchanges between demonstrators and police. My roommate was active in organizing during this time, especially with the campaign for the Civilian Police Accountability Council (CPAC). Through their experiences, I learned how the police showed up, as a matter of routine, to peaceful actions dressed literally for war - in full riot gear with batons, tear gas, and mace all at the ready.

I then saw how mainstream media outlets reported on the violence, which sometimes resulted from these encounters. While positioning themselves as impartial and moderate, implying sympathy for both demonstrators and police, many outlets used subtle but clear rhetoric to make demonstrators look like the aggressors, which was very rarely the case (such as comparisons of a demonstrator throwing a rock at a line of helmeted police to officers macing people in the face at point blank range). Think about it: what unarmed person wants to start shit with a tear gas-toting cop in full riot gear?

Reading An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, I learned about how extra-military settler militia groups have been used by the United States in counterinsurgence combat since before the Revolutionary War. In layman’s terms, that means that civilians in frontier towns were openly encouraged (read: paid) to kill innocent Native Americans, including women, children, and the elderly. Common practices for conquering a village of indigenous people include burning their crops (starving them and crippling them financially), or else, simply attacking their village at night, setting fire to ALL the buildings, and shooting anyone who escaped the fires.

Reading An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, I learned about how extra-military settler militia groups have been used by the United States in counterinsurgence combat since before the Revolutionary War. In layman’s terms, that means that civilians in frontier towns were openly encouraged (read: paid) to kill innocent Native Americans, including women, children, and the elderly. Common practices for conquering a village of indigenous people include burning their crops (starving them and crippling them financially), or else, simply attacking their village at night, setting fire to ALL the buildings, and shooting anyone who escaped the fires.

Anglo civilians were given money for scalps regardless of the victims’ age or gender. I say all this because these settler militia groups are those who became the slave catchers in the next century, eventually becoming the modern American police forces. We respond to news of police violence as if it’s something we haven’t known about. In truth, that violence is a building block of our country. Our culture upholds ideals like conquering (Imperialism) and Manifest Destiny (white supremacy) as quintessential American virtues.

Arriving in Vicksburg, I can’t for the life of me figure out why the Sheriff here needs a para-military SUV to perform their job. What does it say about our country that such weaponized equipment is normal in even a village such as this? I think we have been blind to the violence that is in our blood. But, blindness is not the same as ignorance. Denial is both knowing and not knowing at the same time.

Arriving in Vicksburg, I can’t for the life of me figure out why the Sheriff here needs a para-military SUV to perform their job. What does it say about our country that such weaponized equipment is normal in even a village such as this? I think we have been blind to the violence that is in our blood. But, blindness is not the same as ignorance. Denial is both knowing and not knowing at the same time.

On my first night

in the gallery, which

would be my studio

space, I just sat. I knew

I wanted to install fabric

sculptures in both of the

front windows to then be

projected on. First, I needed

to sit and imagine it. It’s hard

to just sit still, taking in a new place,

letting your senses become acquainted with its

particular details. To be honest, I didn’t stay

all that long. But I was there. I sat and imagined.

in the gallery, which

would be my studio

space, I just sat. I knew

I wanted to install fabric

sculptures in both of the

front windows to then be

projected on. First, I needed

to sit and imagine it. It’s hard

to just sit still, taking in a new place,

letting your senses become acquainted with its

particular details. To be honest, I didn’t stay

all that long. But I was there. I sat and imagined.

That same night, I walked home (my temporary home, that is)

from the studio for the first time. It was twilight and, really, quite

a lovely walk.

The houses here struck me as being so lovely. The people who care for them must really love them well. I felt I might like to live in a house like one of these one day, though I know I would never give it the love required for it to remain beautiful. I felt some sweet nostalgia or homesickness, too; they remind me of some of the houses near my father’s home in the historic district of Rockville, MD. After I leave Vicksburg, I’ll be driving home for the first time since a very short Christmas visit. I miss my family.

For the past year, my studio work has focused on using projection-mapping techniques on highly specific and odd cuts of lumber. While I do dabble in woodworking, myself, a good friend is a serious furniture maker. He mostly makes live-edge pieces - where the milling of the lumber leaves the raw edge/bark from the tree intact. When hanging out in the shop with him, I often find fascinating off-cuts. These pieces are so interesting to me because I can project light onto them in a way that confuses the eye into thinking that the light is coming from within the wood rather than shining onto it. The light can trace the edge between bark and hardwood, making surfaces alternate between emergence and recession.

These pieces are incredibly interesting sculptural objects, even without projection. I brought my favorites with me from Chicago to Vicksburg. On my first full day in the studio, I set them up. Two of them are able to balance on very narrow ends. It’s hard to look at them and imagine that they are not secured in any way, that it’s really just gravity keeping an equilibrium. These things that would often just be trash, arranged in relation to each other, have an effect similar to a Japanese rock garden. Setting them up in this new space felt like establishing the studio as an intimate space for myself. They are an anchor for my thinking; my approaches to each of them remind me of fledgling ideas they gave me about visuals to investigate in future (now, current) works. I’m glad these pieces are here with me in Vicksburg.

Walking around town, I noticed American flags everywhere. There are Trump yard signs as well as Biden signs and those for Senate and local races. There are Black Lives Matter signs and cars with decals of the lower Michigan Peninsula - whose shape resembles a mitten - holding a handgun. Still enamored a bit with the historic houses, I started taking quick shots of all the flags I saw en route from the studio to my house. As I did so, I wondered what each of these American flags represents to the people who fly them on the exteriors of their homes.

Our country’s flag reads to me as a sign of an ownership-based national identity: this land belongs to America. The question in my mind, then, is: who is part of this America that this land belongs to? Are all citizens part of this America? Do all people who live and work here get to belong?

Is it Anglo-centric? Is it Christian? Is the flag a sign of conquering the indigenous peoples who cultivated the land and built the roads before Europeans landed, as the 50 stars seem to signify? Does it represent victory? A victory for whom? A victory over whom? The answers to these questions are clear to me: the American flag represents an Anglo-settler victory over Indigenous Americans.

For many, the American flag is a sign of independence, of victory over British colonial rule. For me, it signifies a brutal evolution in colonial warfare. It is a sign of the (God-given) right of White Christians to live however they please without regard for anyone else - “freedom.”

The irony is that this “freedom” is made possible precisely by the

For many, the American flag is a sign of independence, of victory over British colonial rule. For me, it signifies a brutal evolution in colonial warfare. It is a sign of the (God-given) right of White Christians to live however they please without regard for anyone else - “freedom.”

The irony is that this “freedom” is made possible precisely by the

overwhelming systematic racial and economic oppression of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) persons in this country. This dynamic makes me think of the following words in a way entirely opposed to their original intention: freedom isn’t free.

I doubt that any of the homeowners in these photos intend to broadcast racist sentiments by putting an American flag outside their houses. This perverted version of American “freedom” is, however, what I see when I look around. It’s precisely what I hear and see when those on the right talk about freedom and patriotism while donning the stars and stripes as visibly as possible. It is all I can hear in the rhetoric of the Trump campaign.

My patriotism is an abhorrence of these ideas and a belief that we can do better.

I doubt that any of the homeowners in these photos intend to broadcast racist sentiments by putting an American flag outside their houses. This perverted version of American “freedom” is, however, what I see when I look around. It’s precisely what I hear and see when those on the right talk about freedom and patriotism while donning the stars and stripes as visibly as possible. It is all I can hear in the rhetoric of the Trump campaign.

My patriotism is an abhorrence of these ideas and a belief that we can do better.

Prior to working with the odd off-cuts of lumber, I was making forms out of Organza - a very sheer and highly light-reflective fabric. This fabric box was part of my graduate thesis work. It offers a lot of complex associations - screens, cathode-ray tube televisions, theater, containment, as well as anthropomorphic qualities - within a very simple form. I kept it because I know there’s more to investigate with it.

In Vicksburg, I saw the box as an opportunity to start working through some possible strategies for imagery as I waited for my order of fabric for the new sculptures to arrive from Chicago. It was pleasing somehow to bring back something akin to an “old friend” and try out new methods on it. Revising the past with the perspective of the present always offers new insights to both.

The Mill at Vicksburg:

“In the early 1900s, Vicksburg, MI, was home to one of the most productive paper mills in the region: Lee Paper Mill. Producing over 17 tons of paper per day at its peak, and serving as Vicksburg’s leading employer, Lee Paper Mill was an economic engine that never stopped turning… until it did. The Mill officially shut down in 2001, devastating the community as a reminder of something great in the past that no longer was.

Until sustainable philanthropist Chris Moore swooped in to save it from the wrecking ball in 2014. Now, it’s being resorted to provide the Village of Vicksburg, State of Michigan, and the Midwest Region with something bigger and bolder than ever.”

“In the early 1900s, Vicksburg, MI, was home to one of the most productive paper mills in the region: Lee Paper Mill. Producing over 17 tons of paper per day at its peak, and serving as Vicksburg’s leading employer, Lee Paper Mill was an economic engine that never stopped turning… until it did. The Mill officially shut down in 2001, devastating the community as a reminder of something great in the past that no longer was.

Until sustainable philanthropist Chris Moore swooped in to save it from the wrecking ball in 2014. Now, it’s being resorted to provide the Village of Vicksburg, State of Michigan, and the Midwest Region with something bigger and bolder than ever.”

A major renovation project in a disused factory of great architectural historical significance? Yes please! When I applied for the Prairie Ronde Artist Residency, I imagined spending my days running around a dark industrial quasi-wasteland to see what magic I could uncover with my projector. It turns out, they don’t really turn artists loose in 400,000 sq. ft. active construction and remediation sites. Go figure. But I have been able to tour the mill a couple of times. The second time, John Kern, who has been my primary host during my residency, took me and Chris (the furniture maker from whom I scavenge off-cuts) around the place. I had a feeling these two guys would geek out on the details of the original construction as well as the scope of the rehab work. I was right. It left me free to get lost in the light.

The floor boards are all 3 x 4 planks of old-growth red pine. The basement feels like catacombs. There is a pile of rubble outside that is at least 30 feet high and 100 feet wide. These photos utterly fail to capture the scale of the place.

This mill was the center of the town for its entire existence up until 2001. Think about it. Residents' lives were marked by shift whistles 3 times per day. The train tracks that run through town because of the mill still deliver trains - often more than one per hour - throughout the day and night. I heard one account which said that residents could tell what kind of paper was being made by the color that the small creek that runs through town was turned by that day’s run-off. Polish immigrants moved here from Chicago to obtain work. These jobs were so secure that people started immigrating directly from Poland to Vicksburg. The part of town directly across the highway from the mill, where I’m staying, was known as Polishtown. I still have not asked - how hard was Vicksburg hit economically after the mill shut down in 2001? How did it survive the 2008 recession? I only see a few small businesses around town. No real industry, to speak of. What drives the economy today? There’s still time to ask.

As I’ve finished reading The New Jim Crow, by Michelle Alexander, I can’t help but see what could have been an early prison building when looking at the outside of the mill. Granted, any prison with many windows would likely not be very effective. Still, the fortress quality of the architecture combined with my thoughts of “freedom,” and “who does the idea of America include,” leads me to think of the people who worked here as less than free.

Capitalism has always depended upon the plentiful availability of free or cheap labor. We are told that Capitalism means that anyone can succeed if they work hard enough. Simply put, that’s a lie. It assumes an even playing field, which neither now nor ever has existed. Those who succeed in America may, in fact, work hard. But that alone is not how they succeed. They have support from family, can afford education, they know someone who gives them a shot, something. No one succeeds completely on their own. For many, especially those at the highest echelons of the corporate oligarchy, success is a birthright. It’s never earned.

On the other side, many racially and economically oppressed Americans don’t even have the luxury of working hard. They live in job deserts or face permanent legalized discrimination based on a felony label - a label which is nearly impossible to avoid for many, especially black and brown men living in ghettoized communities. In 1999, just 992 African American men earned bachelor’s degrees from Illinois state universities. That same year, 7000 (that’s 7 times the first number) black men were released from Illinois prisons - for drug offenses alone. It is not a sad, unfortunate side effect of the War on Drugs that so many black men are imprisoned and labeled felons for life. It is precisely the goal of “tough on crime” policies to produce this outcome, and it is hard to imagine a more effective system.

When I see the exterior of this mill, yes, it provided an economy and a life for an entire town for over a century. I just can’t help but wonder how disproportionately the owners of the mill may have benefited financially from the blood, sweat, and tears of their workers. The mill provided security, but, for most capitalist-based companies, keeping costs down through paying as little as possible, especially to disadvantaged groups - like Polish immigrants - is a critical business strategy. In that kind of light, it’s hard to see this building as totally unrelated to a prison. Both reflect a larger system of oppression.

Another night in the studio/gallery

working with the fabric box. This

time, I used color. I wanted the

animation to look like flames taking

over the box and then becoming just

a blue-gray smoke. It was really

exciting in person, but, as

sometimes happens with my work,

documentation falls short.

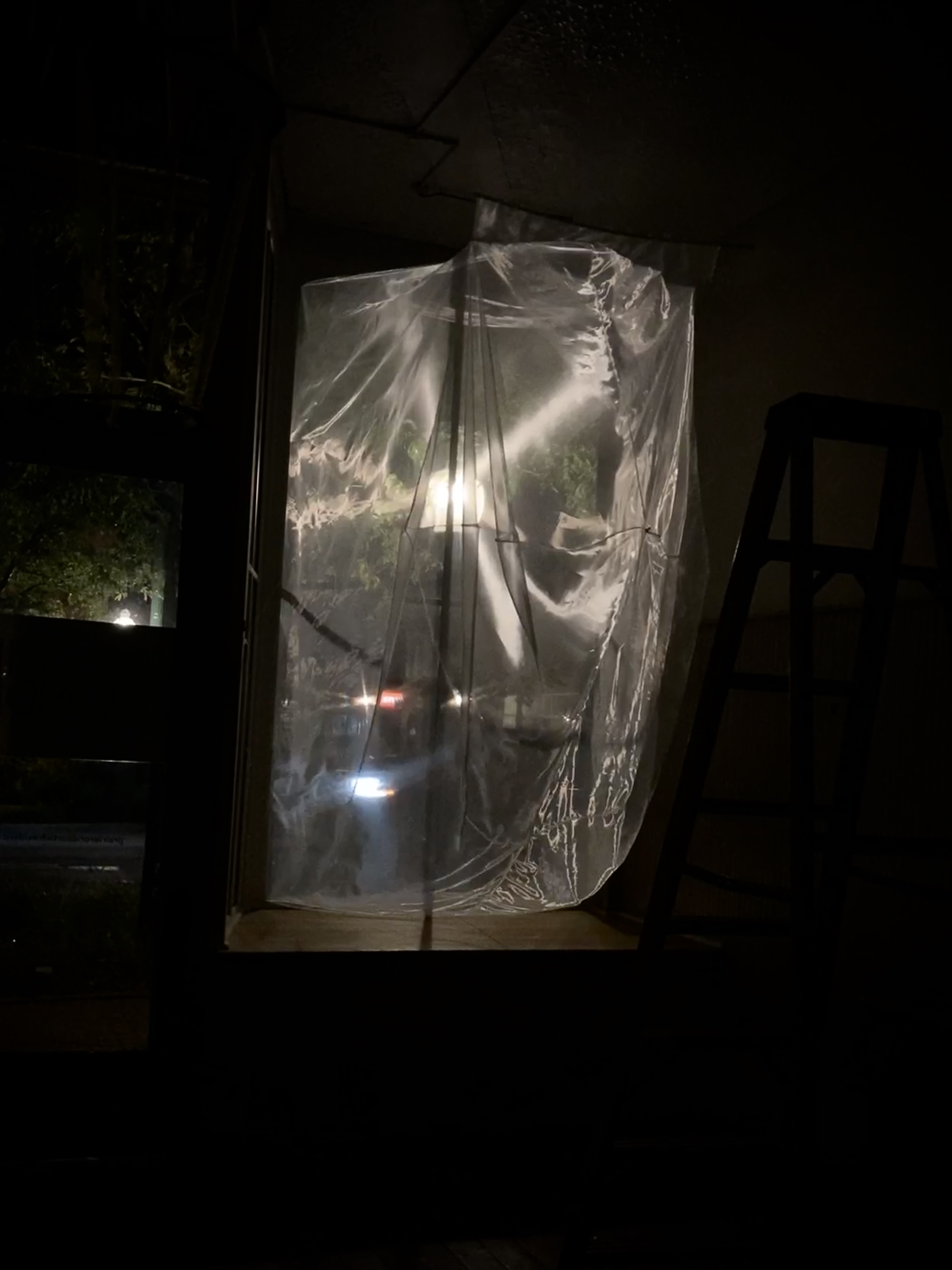

Eventually, I got my order of organza from Chicago and started constructing the large fabric sculptures for the installation. Now, I can mend a shirt, but I’m not an experienced seamstress. The most involved thing I’ve ever made out of fabric was the series of boxes I’ve already discussed on this page. Having experience with this specific fabric definitely helped, but making two giant window sculptures was a daunting task. I used nearly all of the 300 yards of fabric I purchased. I was a bit stressed as I worked because I knew I didn’t have enough extra fabric to start one of these sculptures over again if I made a dire mistake. There were times when I was able to zone out, going through the motions of sewing. Overall, though, it was a frustrating process. Organza is polyester. It slips and slides all over itself, which makes measuring, marking, creating seams, and the actual sewing quite difficult.

I had initial sketches and measurements for the sculptures, which definitely helped the process along. There were times, though, when I had to affix the fabric to the windows in order to see how the form should develop. This involved wrapping myself in tens of yards of fabric before ascending a tall ladder atop 3 ft high window platforms - I felt like a little kid who dressed in their mother’s wedding gown and tried to climb a tree. Wrap up, measure, down, sew, wrap up, look, think, down, sew, etc.

I started to refer to the sculptures as “window socks.” The soft funnel-like shape reminded me of a windsock, so I just changed wind to window.

Once I had the first window sock up, I went outside to look at it from the street. Man, was I disappointed! I know that the way I work allows for things to change as they come into being. I knew that the sculptures would not look exactly like my sketches. Things always evolve as they’re made. I just know that I have the ability to make things work and that, often, the developments that I could never predict have the most important impact on the work. Not to be confused with working in an accidental fashion, harnessing discovery as a part of my process ensures that I remain engaged and responsive to the site and materials at all times. It means that the potential is present for something to happen beyond what I could previously conceive. The point of making art for me has a lot to do with uncovering that which I cannot yet imagine as possible. So, uncertainty in work is a good thing. Also, though, it means it can totally fail. When making work for a show, that can be stressful. And, while I want the work to be something more than what I planned, that moment where I am confronted with what actually is, as opposed to what I had imagined, can be a real kick in the gut. That’s what happened here. Dualling voices of “You’re failing,” and “You can do this! You always pull things off because you never give up!” are what follow that gut kick. I take a break and I look for ways to engage with the sculpture that might reveal something in it that I have not yet seen. I decide that there are a couple of corners of fabric that don’t appear to be attended to. They just hang there. Maybe if I pull them to the sides and just do something to address them, the form will feel more resolved.

The next day, that’s exactly what I did. And, it totally worked! As soon as those floppy corners were resolved, the piece had more folds and layers, and was just doing a lot more for me. So, I got kicked in the gut one day and just felt a huge sense of optimism and self-confidence the next.

That night, I started working with the projections for the first time.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When approaching the animation, I knew the imagery would need to be incredibly simple. Like, straight lines kind of simple. This is due to the complexity of these fabric sculptures. When projected onto a complex form, images bend and warp according to that form. If I were to project shapes and images that were already complex onto these sculptures, the details of both would be lost. The muddled result would either read as boring or as stimulus overload. On the other hand, when I project extremely simple imagery like parallel lines or concentric squares, the sculpture bends the lines as the light lands on its various planes. The form of the sculpture is revealed by the light of the image, and the image is made more interesting, altered, and bent by the sculpture. In this situation, we’re also dealing with reflection from the glass and wall, shadow created by the alcove, and other light sources on the street, including those from passing cars.

Particularly because of the large amount of competing light in the area, I chose to use black and white imagery. This is the highest value contrast possible and has the best chance of being visible even with other light present. I did experiment with high contrast color one night, just to make sure my thesis was correct. It was. Black and white is the most visible. Also, it allows the fabric form to be the star of the show by keeping shadows as fully image.

The black and white palette works very well thematically, as well. Knowing that extremely reduced imagery is what would work best with this project, I walked around Vicksburg loosely thinking about what imagery here could be brought into the work. One thing that really struck me was the exterior of the Mill. Five stories high and as wide as I can see when standing in front of it, full of dark windows. It’s an imposing fortress-like grid. As I mentioned above, it reminded me somewhat of a prison. So, I thought, what about vertical black and white stripes as a loose visual reference to jail cells? As a starting point for an animation, this is the kind of broad visual reference I like to start with. Then, I see how I can make it fit specifically with the site, the object it’s projected onto, etc. In this work, however, I’m taking on another layer of specific context in the form of Vicksburg, and, by extension, America. Given the country’s and my own intense focus on interrogating both seen and unseen systems of racial oppression at this moment, I felt this area could be very productive to investigate with this work.

At the moment, I’m still working on the animation. It is my goal to move the vertical black and white stripes into a sort of grid-like image that will be a clear reference to the Mill. I believe that that connection helps ground the abstract animation in a very concrete way to this place for viewers here. Maybe, even, it will help people here to feel that this work includes them. That they can use this as a resource for self-inventory and sharing with others around them. This town is not removed from what is happening in our country. It is very actively a part of it. Freedom for some comes through the subjugation of others. We are each of us responsible for seeing how our inaction supports this terrible status quo.

I had initial sketches and measurements for the sculptures, which definitely helped the process along. There were times, though, when I had to affix the fabric to the windows in order to see how the form should develop. This involved wrapping myself in tens of yards of fabric before ascending a tall ladder atop 3 ft high window platforms - I felt like a little kid who dressed in their mother’s wedding gown and tried to climb a tree. Wrap up, measure, down, sew, wrap up, look, think, down, sew, etc.

I started to refer to the sculptures as “window socks.” The soft funnel-like shape reminded me of a windsock, so I just changed wind to window.

Once I had the first window sock up, I went outside to look at it from the street. Man, was I disappointed! I know that the way I work allows for things to change as they come into being. I knew that the sculptures would not look exactly like my sketches. Things always evolve as they’re made. I just know that I have the ability to make things work and that, often, the developments that I could never predict have the most important impact on the work. Not to be confused with working in an accidental fashion, harnessing discovery as a part of my process ensures that I remain engaged and responsive to the site and materials at all times. It means that the potential is present for something to happen beyond what I could previously conceive. The point of making art for me has a lot to do with uncovering that which I cannot yet imagine as possible. So, uncertainty in work is a good thing. Also, though, it means it can totally fail. When making work for a show, that can be stressful. And, while I want the work to be something more than what I planned, that moment where I am confronted with what actually is, as opposed to what I had imagined, can be a real kick in the gut. That’s what happened here. Dualling voices of “You’re failing,” and “You can do this! You always pull things off because you never give up!” are what follow that gut kick. I take a break and I look for ways to engage with the sculpture that might reveal something in it that I have not yet seen. I decide that there are a couple of corners of fabric that don’t appear to be attended to. They just hang there. Maybe if I pull them to the sides and just do something to address them, the form will feel more resolved.

The next day, that’s exactly what I did. And, it totally worked! As soon as those floppy corners were resolved, the piece had more folds and layers, and was just doing a lot more for me. So, I got kicked in the gut one day and just felt a huge sense of optimism and self-confidence the next.

That night, I started working with the projections for the first time.

When approaching the animation, I knew the imagery would need to be incredibly simple. Like, straight lines kind of simple. This is due to the complexity of these fabric sculptures. When projected onto a complex form, images bend and warp according to that form. If I were to project shapes and images that were already complex onto these sculptures, the details of both would be lost. The muddled result would either read as boring or as stimulus overload. On the other hand, when I project extremely simple imagery like parallel lines or concentric squares, the sculpture bends the lines as the light lands on its various planes. The form of the sculpture is revealed by the light of the image, and the image is made more interesting, altered, and bent by the sculpture. In this situation, we’re also dealing with reflection from the glass and wall, shadow created by the alcove, and other light sources on the street, including those from passing cars.

Particularly because of the large amount of competing light in the area, I chose to use black and white imagery. This is the highest value contrast possible and has the best chance of being visible even with other light present. I did experiment with high contrast color one night, just to make sure my thesis was correct. It was. Black and white is the most visible. Also, it allows the fabric form to be the star of the show by keeping shadows as fully image.

The black and white palette works very well thematically, as well. Knowing that extremely reduced imagery is what would work best with this project, I walked around Vicksburg loosely thinking about what imagery here could be brought into the work. One thing that really struck me was the exterior of the Mill. Five stories high and as wide as I can see when standing in front of it, full of dark windows. It’s an imposing fortress-like grid. As I mentioned above, it reminded me somewhat of a prison. So, I thought, what about vertical black and white stripes as a loose visual reference to jail cells? As a starting point for an animation, this is the kind of broad visual reference I like to start with. Then, I see how I can make it fit specifically with the site, the object it’s projected onto, etc. In this work, however, I’m taking on another layer of specific context in the form of Vicksburg, and, by extension, America. Given the country’s and my own intense focus on interrogating both seen and unseen systems of racial oppression at this moment, I felt this area could be very productive to investigate with this work.

At the moment, I’m still working on the animation. It is my goal to move the vertical black and white stripes into a sort of grid-like image that will be a clear reference to the Mill. I believe that that connection helps ground the abstract animation in a very concrete way to this place for viewers here. Maybe, even, it will help people here to feel that this work includes them. That they can use this as a resource for self-inventory and sharing with others around them. This town is not removed from what is happening in our country. It is very actively a part of it. Freedom for some comes through the subjugation of others. We are each of us responsible for seeing how our inaction supports this terrible status quo.