WONDER VALLEY

2023

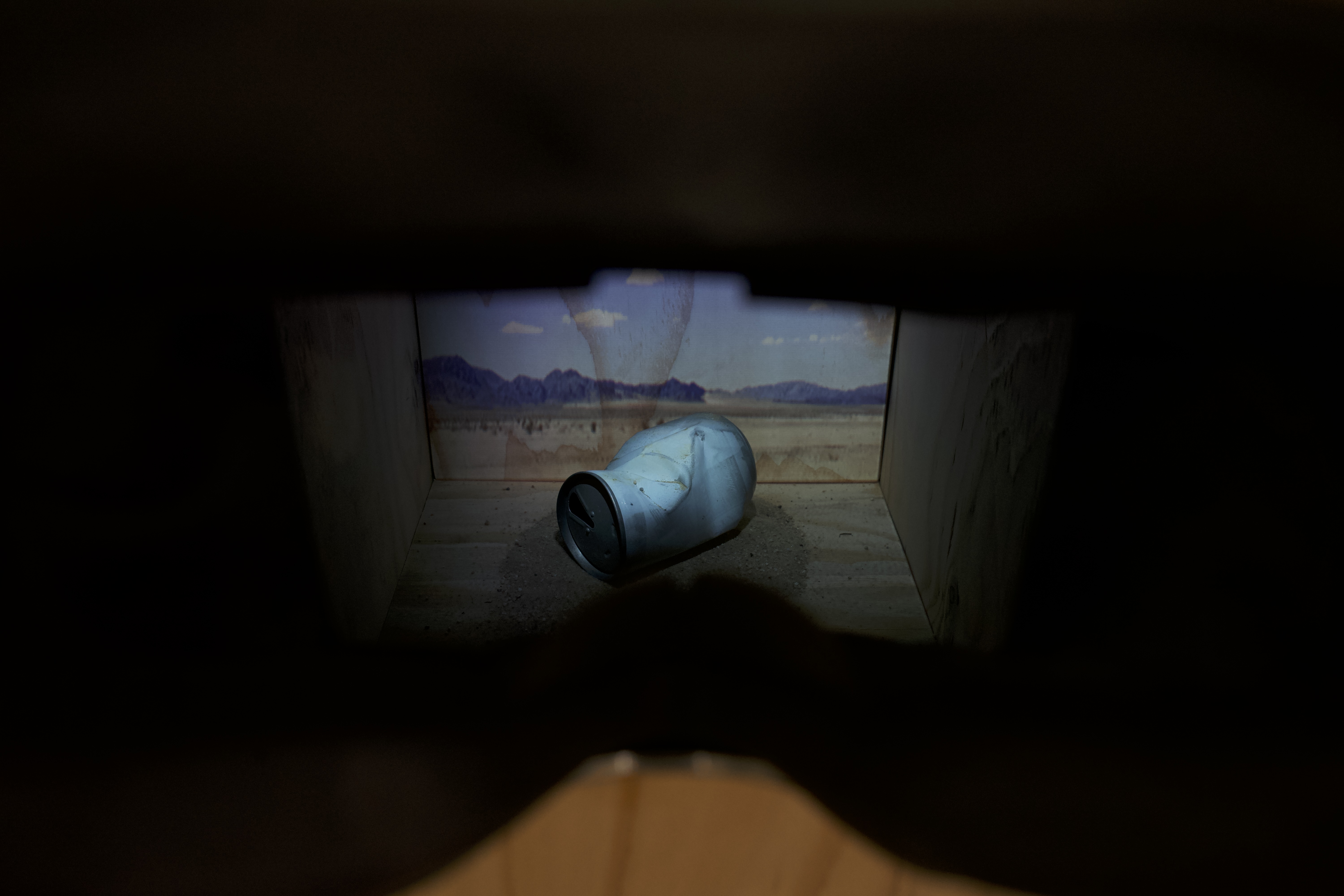

Projection-Mapped Abstract Animation, Found Antique Budweiser Can, Plywood Housing, View Port (Steel, Rubber, Plastic, Fabric), Mojave Desert Sand, 12x34x18 inches, 3:00

This piece was made using materials and footage collected while in residence at High Desert Test Sites, part of AZ-West, Joshua Tree, CA and was exhibited in Going Steady at Carnation Contemporary, Portland, OR, Dec. 2-17, 2023.

Access to the SE Portland Tool Library made this work possible.

Projection-Mapped Abstract Animation, Found Antique Budweiser Can, Plywood Housing, View Port (Steel, Rubber, Plastic, Fabric), Mojave Desert Sand, 12x34x18 inches, 3:00

This piece was made using materials and footage collected while in residence at High Desert Test Sites, part of AZ-West, Joshua Tree, CA and was exhibited in Going Steady at Carnation Contemporary, Portland, OR, Dec. 2-17, 2023.

Access to the SE Portland Tool Library made this work possible.

Wonder Valley, 2023, is an abstract animation projection-mapped onto an antique Budweiser can housed within a wall-mounted viewing box and outfitted with a face rest view port.

The box came first. It was a result of thinking through new ways to offer exciting and unique immersive moving light viewing experiences that are well-suited for display in a fully lit gallery surrounded by other artworks.

The can came next. In September-October 2023, I was a work-trade artist-in-residence at High Desert Test Sites, part of Andrea Zittel’s AZ-West in Joshua Tree, CA. While there, some of us residents as well as staff took a drive out to Wonder Valley, CA, to look at permanent HDTS works who live within the desert. This locale, specifically, has been referred to by artist Jack Pierson as “a place known for those who drop off the edge of civilization.”

Closer to Joshua Tree and Twenty-Nine Palms, there are BLM lands where people go to race ATVs, throw massive outdoor parties, or just sleep in their cars, building a fire to try to keep warm at night. Wonder Valley is so remote that it fails to attract such groups. However, its remoteness also makes it possible to use the land however you want, BLM or not.

Here, in the heat of a late summer midday, the four of us walked through the fine, pale sand to find our way to the artworks as they stand surrounded by purple mountains in a distance that, in those flats, feels impossibly close at hand. Strewn around in the sand amongst the rocks and creosote is evidence of passersby: charred logs and, every now and then, a bit of random detritus. Ava picked up a white can, commenting on its appearance. She dropped it and we walked on. I got to thinking about the whiteness of it. An old pull tab can from 1980, it had been bleached by the brutal desert sun for over 40 years. The ghost of the Budweiser logo was still visible from certain angles. I went back and picked it up.

In that beautiful and desolate place, the contrast of advertising campaigns - majestic Clydesdales and the Marlboro Man, remnants of the American cowboy and Manifest Destiny - against a country dotted with abandoned gold mines and decrepit jackrabbit homesteads, I was struck by the fallacy of it all, and the sorrow. This humble and discarded object quietly held a small part of a much larger story: the stripping of nature, indigenous cultures, the lives and freedom of all peoples of color, and humanity, even of the various waves of settlers and opportunists. With the massive military complexes nearby, I couldn’t help but imagine a Vietnam veteran, home for a handful of years, sitting in the desert by himself in the night with a small fire, a tepid Bud in his hand, and few options for any kind of a future. Buying the promises they sell us is sometimes a speedy path to misery and destitution.

Reading Rebecca Solnit’s books River of Shadows and Savage Dreams, the former a treatise on western culture’s rupture from time and place, the latter a detailing of anti-nuclear efforts in the US and the origination of Yosemite National Park, had me observing even more closely than usual the landscape tourism that is our National Parks system. First, the original inhabitants were killed or pushed off. Then, places were re-named by white settlers to make them into wild and virginal substitutes for Eden, erasing their existence as generational homes, holy sites, and the beneficiaries of centuries of human stewardship.

The box came first. It was a result of thinking through new ways to offer exciting and unique immersive moving light viewing experiences that are well-suited for display in a fully lit gallery surrounded by other artworks.

The can came next. In September-October 2023, I was a work-trade artist-in-residence at High Desert Test Sites, part of Andrea Zittel’s AZ-West in Joshua Tree, CA. While there, some of us residents as well as staff took a drive out to Wonder Valley, CA, to look at permanent HDTS works who live within the desert. This locale, specifically, has been referred to by artist Jack Pierson as “a place known for those who drop off the edge of civilization.”

Closer to Joshua Tree and Twenty-Nine Palms, there are BLM lands where people go to race ATVs, throw massive outdoor parties, or just sleep in their cars, building a fire to try to keep warm at night. Wonder Valley is so remote that it fails to attract such groups. However, its remoteness also makes it possible to use the land however you want, BLM or not.

Here, in the heat of a late summer midday, the four of us walked through the fine, pale sand to find our way to the artworks as they stand surrounded by purple mountains in a distance that, in those flats, feels impossibly close at hand. Strewn around in the sand amongst the rocks and creosote is evidence of passersby: charred logs and, every now and then, a bit of random detritus. Ava picked up a white can, commenting on its appearance. She dropped it and we walked on. I got to thinking about the whiteness of it. An old pull tab can from 1980, it had been bleached by the brutal desert sun for over 40 years. The ghost of the Budweiser logo was still visible from certain angles. I went back and picked it up.

In that beautiful and desolate place, the contrast of advertising campaigns - majestic Clydesdales and the Marlboro Man, remnants of the American cowboy and Manifest Destiny - against a country dotted with abandoned gold mines and decrepit jackrabbit homesteads, I was struck by the fallacy of it all, and the sorrow. This humble and discarded object quietly held a small part of a much larger story: the stripping of nature, indigenous cultures, the lives and freedom of all peoples of color, and humanity, even of the various waves of settlers and opportunists. With the massive military complexes nearby, I couldn’t help but imagine a Vietnam veteran, home for a handful of years, sitting in the desert by himself in the night with a small fire, a tepid Bud in his hand, and few options for any kind of a future. Buying the promises they sell us is sometimes a speedy path to misery and destitution.

Reading Rebecca Solnit’s books River of Shadows and Savage Dreams, the former a treatise on western culture’s rupture from time and place, the latter a detailing of anti-nuclear efforts in the US and the origination of Yosemite National Park, had me observing even more closely than usual the landscape tourism that is our National Parks system. First, the original inhabitants were killed or pushed off. Then, places were re-named by white settlers to make them into wild and virginal substitutes for Eden, erasing their existence as generational homes, holy sites, and the beneficiaries of centuries of human stewardship.

The parks were created to protect exceptionally beautiful or important lands from the ravenous consumption of nature that took place in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Some places only achieved protected status after decades of lobbying by environmental groups and massive private financial contributions that the government was happy to accept. Now, hordes of people make pilgrimages to these sites every year for the express purpose of driving by them, or stopping briefly to take snapshots: taking a photo yourself of a place that’s been endlessly photographed by others, without ever even setting foot on the actual land. [My friend, the artist Erinn Kathryn, has an incredible series looking at exactly this phenomenon.] Nature as spectator sport. What a full-circle reflection of Solnit’s rupture. And corporations continuously increase profits as all of our time, our leisure, our relationships, have become financialized via neoliberalist policy and social media.

I realized quickly that the can needed to be inside the box. The box makes the can a symbol. We can see it, experience its physical properties, especially as the animation moves across its form, but we can’t touch it or be in the same space as it. We are spectators. And, isn’t that exactly what so many of us crave? The feeling of being with beautiful places without actually being in them? Or, giving up our comfort? Without breaking the digital barrier? The pleasure of consumption without the inconvenience of relationship or vulnerability? The last detail was the sand. Before leaving HDTS, I’d gone back to the spot where we found the can to collect sand. I brought it, along with other desert treasures, talismans of place, back to Portland with me in the back of my Camry.

The box took some engineering. Literally. How to make a light-tight box with a projector inside it was a pretty fun puzzle to solve. Fortunately, my wonderful partner is an engineer and has become a collaborator on the construction of my works. Once designed, I used tools from the SE Portland Tool Library to construct it. While carefully made, I chose to leave the box unfinished inside and out. This was so that it’s clear that the box is a vessel, not the main attraction. The viewport took a lot of planning. It was the way people would relate to the whole piece. It had to look and feel just right and give the right viewing angle and range. A new HDTS friend who also lives in Portland helped me by fabricating the steel shaft, contouring it to the VR headset face mount I’d bought for the rim. It took a lot of doing on my part to figure out how to attach all the components and mount it to the box so that it was sturdy, comfortable, and light-tight.

Last came the video. I initially planned only to have animation on the can itself. Using simple white lines moving over a form reveals the complexity of that form in a way that never fails to excite me. Very quickly, though, I remembered the video of those purple mountains that frame Wonder Valley I’d taken from the back seat of the car as we drove out to the artworks that day. That’s the video playing behind and over the can. When installing Wonder Valley, I poured the sand under the can, wanting to recreate as much of its original place as possible.

This work is, in some ways, very different from my previous works. I usually put the viewer in the environment with the objects and light; a bodily relationship. Here, the work and the viewer are kept apart. It doesn’t feel that way, though. Viewing this piece feels immersive, protected, and transportive. Encountering it within the gallery, as it glows from across the room with tempting hints of its dancing insides, feels exciting and playful. It holds the histories of early cinema (kinetoscopes, aka “peep shows”), tourism (coin binoculars), national parks, postcards, and advertising, most of which are the grandchildren of white supremacist imperialism, as well as the newness of digital media and finely-tuned projection-mapping. There’s a strange nostalgia and sadness to it, along with the thrill of the spectacle and oddity offered by the work itself. Mostly, though, what I feel in it is loss. It’s the loss of indigenous Americans who were and continue to be exterminated in the name of imperialist delusions, and the loss of humanity within the settler colonists themselves. Imperialism pays hush money to the privileged classes, but that does not exempt us from enslavement. We just believe the lie that we’re free. And we stand by, believing we’re blameless, while people are caged and slaughtered.